Four Historic Women in Construction

Quick question… What did Puritan families send to mourners before a funeral service?

Not up on your eighteenth-century funeral services trivia?

I’m not surprised. There are probably very few people in this world who can answer that question.

One of those few people would be Laurel Thatcher Ulrich…who you probably also can’t answer any questions about. Laurel is a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, who embodies her most famous quote: “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” You wouldn’t know this now, due to how the quote has been taken out of context, but Ulrich never meant her quote to mean that only rule-breaking women are the only ones able to leave a legacy. Ulrich’s comment written in a 1976 scholarly article on Puritan funeral services meant that influential women throughout history have historically been disregarded.

Although they might not be household names, trailblazing women invented things we use every day like car heaters, the automatic dishwasher, the drip coffee machine, and countless other important and life-changing inventions and engineering marvels.

Disruptor: a person or thing that prevents something, especially a system, process, or event, from continuing as usual or as expected: a company that changes the traditional way an industry operates, especially in a new and effective way:

Here at Beck Technology, we like to refer to these ‘ill-behaved' women as disruptors. In our industry, there are plenty of women who disrupted and continue to disrupt the AEC status quo, so in honor of Women’s History Month, we’d like to highlight of few of the first ladies of construction.

Julia Morgan— First Woman to Get an Architecture License in California

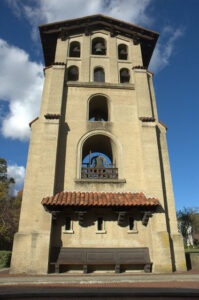

Julia Morgan designed the El Campanil Bell Tower in 1903. Photo courtesy of Our Oakland.

Julia Morgan designed the El Campanil Bell Tower in 1903. Photo courtesy of Our Oakland.Julia Morgan is the most written about and most widely recognized pioneering woman in the construction industry. She traveled a long road, but her drive and determination paid off, even long after she passed. In 1894, Julia graduated with honors from the University of California Berkeley with a Bachelor of Science in civil engineering. She was the first woman to do so.

Upon graduating, Julia worked for a year before going to Paris, France to attempt an acceptance into the prestigious architectural school École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. The famed art school opened its doors to women for the first time in 1897.

It took Julia three attempts on the entrance exam before being admitted, where on the third, she placed 13th out of 376. Though unable to finish due to her age—the school placed age limits on students and Julia was 30—she was the first woman to earn a certificate in architecture from the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts.

After returning to the States, Julia became known for her use of reinforced concrete. Her first project using her innovative method was the 72-foot bell tower located on the campus of Mills College in Oakland, California commissioned in 1903. The bell tower survived the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 and still stands today. Sustaining no damage, Julia’s reputation grew quickly and she went on to design countless buildings. Two of her most notable designs are the (redesign) of the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco and Hearst Castle—now a National Historic Landmark and California Historical Landmark.

In 1904, Julia was the first woman to get an architecture license in California, and in 2014, she was posthumously awarded the American Institute of Architects’ AIA Gold medal. She was the first woman to receive the organization’s highest award.

Emily Roebling—Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge

“I have more brains, common sense, and know-how, generally than any two engineers civil or uncivil that I have ever met, and but for me, the Brooklyn Bridge, would never have had the name Roebling in any way connected to it!” -Emily Roebling

Though she never technically held the title, it is widely accepted that Emily Roebling served as Chief Engineer during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge—at the time the longest-span suspension bridge in the world, and the first bridge to be built using steel cables.

Emily Roebling took over for her husband as supervisor of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1872

Emily Roebling took over for her husband as supervisor of the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1872Emily’s husband, civil engineer Washington Roebling, replaced the late John Augustus as construction supervisor of the bridge in 1896. However, not soon after, Washington became very sick with decompression sickness due to a prolonged study of underwater foundations. Emily took over his work in 1872 overseeing every aspect of the bridge’s construction.

The bridge was completed in 1883 and Emily took the maiden voyage riding a carriage across. According to Britannica.com, “In a stirring dedication speech on opening day, the philanthropist, political reformer, and rival steelmaker Abram S. Hewitt declared that the new bridge would “ever be coupled” with the thought of Emily Warren Roebling” proving that even though Emily was never officially Chief Engineer, she certainly stood up to the plate.

Sarah Guppy—First Women to Patent a Bridge

Construction of the Menai Bridge was completed in 1826.

Construction of the Menai Bridge was completed in 1826.One woman who bridged the gap, literally and figuratively, between the challenges women faced both politically and socially was Sarah Guppy. An English inventor and engineer, Sarah was the first woman to patent a bridge design. Her 1811 “New Mode of Constructing and Erecting Bridges and Railroads without Arches” patent was a way of using piling for the building of a suspension bridge. The patent reads:

“I do fix or drive a row of piles, with suitable framing to connect them together, and behind these I do fix, or drive, and connect, other piles or rows of piles and suitable framing, or otherwise, upon the banks of the said river or place.”

Due to the restrictions on women at the time, Sarah was never able to use her design; however, she allowed the free use of it to Thomas Telford who used this innovative design when building the Menai Suspension Bridge in Wales. It is written that Thomas Telford never gave Sarah credit for the design.

Sarah carried on to file 10 patents during her life.

Louise Blanchard Bethune—The First Professional Female Architect in the United States

Louise Blanchard Bethune was a woman of many firsts in the AEC industry. She began her apprenticeship in 1876 taking a draftsman (draftswoman) position at Richard A. Waite architectural firm in Buffalo, New York. In 1881, she opened her firm, specializing in Romanesque Revival design. With her partner, Robert A. Bethune, her firm designed hundreds of buildings in New York, including the Buffalo Public Schools, the 74th Regiment Armory, Lockport High School, the East Buffalo Live Stock Exchange, and the Hotel Lafayette as the most notable.

During its heyday, the Hotel Lafayette, designed by Louise Blanchard Bethune was one of the top nicest hotels in the U.S.

During its heyday, the Hotel Lafayette, designed by Louise Blanchard Bethune was one of the top nicest hotels in the U.S.In 1885, Louise joined the Western Association of Architects, making her the first woman admitted to any architectural professional association. She also served as vice president of the Western Association of Architects for one term. Louise went on to become the first woman admitted to the American Institute of Architects in 1888 and the first woman member of the Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

GoConstruct.org writes that in 2020 women made up 14% of the workforce in the construction industry. From the time these historical women in construction were pioneers to today, we’ve come a long way, baby. Let’s keep the momentum going!

*If you are just dying to know the answer to our question about Puritan funeral services, the answer is gloves. Who would have guessed?

For support and professional resources for women who work in construction check out the National Association of Women in Construction.

-1.png?width=112&height=112&name=image%20(4)-1.png)