4 Construction Trailblazers

Although the construction industry can often be associated with phrases like “old-fashioned” or “slow to change,” the reality is that construction is a world where barriers are broken every single day—both literally and figuratively! Whether it’s building something that was previously thought impossible, like the Eiffel Tower, or entering into a field that was previously inaccessible, like Julia Morgan (the first woman to get an architect license in California), the industry is not quite as stagnant as many would have you believe.

That’s why we want to highlight some of the lesser-known trailblazers in construction. Typically, the word trailblazer is defined as “a pioneer; one who innovates,” but another definition is “a person who makes a new track through wild country.” And frankly, many of the people you’ll soon read about below encapsulate that second definition much more than the first. Innovation on its own is one thing. But innovation in the face of difficult, even inhospitable environments is another thing entirely. That’s exactly what these trailblazers were often up against. They weren’t just coming up with new ideas—they were often going down a path no one had ever taken before, filled with dozens of obstacles along the way.

Louis Kahn

Louis Kahn was one of the most influential architects of our time.

Louis Kahn was one of the most influential architects of our time.Though not necessarily a household name in the way Franklin Lloyd Wright is, Louis Kahn was a well-respected architect in his own right, known for mid-century designs often ahead of his time. Kahn was born to a poor Jewish family in Russia and later emigrated to the United States at the age of six. He entered the field of architecture through his passion for high school art, which led to him getting his Bachelor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania School of Fine Arts. After graduating, Kahn went on a tour of Europe, a trip that would influence much of his later work.

Kahn’s most well-known and innovative work, however, wouldn’t come until the 1960s in the form of the renowned Salk Institute for Biological Studies. Kahn was commissioned to design this project by the inventor of the polio vaccine, scientist Jonas Salk. Kahn’s work on the Salk Institute was groundbreaking for two reasons. First, both he and Salk helped dismantle discriminatory residency laws—at the time, the Californian plot of land they would be building on was located in the neighborhood of La Jolla, which prevented minorities—including Jews—from owning homes. Salk and Kahn, both Jewish, informed the neighborhood that they would not agree to build the institute there unless they removed these residency laws. Although it wouldn’t happen until a year after the institute had opened its doors, La Jolla ultimately complied with this request, ending an era of segregation in their neighborhood.

In addition to changing the landscape of La Jolla, Kahn’s design for the Salk Institute was positively futuristic in its melding of art and sustainability. Salk had asked Kahn to create a building “worthy of a visit by Picasso,” and as a result, Kahn took inspiration from places such as the monastery of St. Francis of Assissi. Perhaps even more importantly, Kahn’s design would be considered LEED-certified today, even though there were no such ratings at the time the institute was developed. Kahn cleverly planned for underground cisterns to collect and reuse rainwater, as well as offices built to siphon off the ocean breeze and green roofs on top of the building. To read more about Kahn’s seminal work, click here.

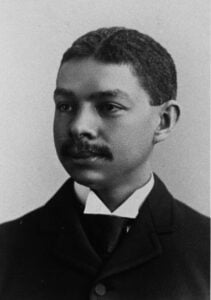

Robert Robinson Taylor

Robert Robinson Taylor was the first African American who enrolled at MIT and the first Black accredited architect in 1892.

Robert Robinson Taylor was the first African American who enrolled at MIT and the first Black accredited architect in 1892.Robert Robinson Taylor was the author of many “firsts.” Born in 1868 to a father immersed in the building trade, Taylor would go on to become the first Black graduate from MIT and the first credentialed academically trained Black architect in the United States.

Taylor learned much about the industry through his father, who had built a successful career as a contractor; his specialty resided in cargo ships that would then journey along the trade routes between the U.S. and South America. Taylor worked in his father’s business after graduating high school, but it was eventually agreed between the two of them that he needed to formalize what he was learning by attending college. Although he originally wanted to attend Lincoln University near Philadelphia, he ultimately chose to go to MIT, which was known for having the best program in architecture available at that time. Taylor excelled at MIT and left with honors, and was subsequently recruited by educator Booker T. Washington to develop the Tuskegee Institute, a school focusing on practical trades for the Black community.

Taylor would go on to design most of the early buildings for the Tuskegee Institute. He was largely influenced by the Colonial Revival style, resulting in structures both functional and beautiful. His most well-known work for the institute, “The Chapel,” was the first building in Macon County, Alabama to use interior electrical lights. The building would also partially inspire Ralph Ellison’s novel The Invisible Man.

Denise Burgess

Since taking over the family construction business, Denise Burgess has become an influential resource in downtown Denver's development.

Since taking over the family construction business, Denise Burgess has become an influential resource in downtown Denver's development.

Originally intending to pursue a career in broadcast management, Denise Burgess hadn’t been in her field for long before her father, Clyde Burgess, asked her to look over some marketing materials for the family HVAC business he ran. Founded in 1974, Clyde began designing and installing HVAC systems in Denver, Colorado, because he wanted to do a better job at it than the company he was with at the time. Thanks to his experience in the military, Burgess would end up landing several federal HVAC contracts, and the business grew exponentially.

Before long, Burgess found herself working right alongside her father after he asked for her help with marketing, and even went back to college to get a certificate in construction management. As a result, Burgess decided to move away from the HVAC portion of the business and focus harder on quality assurance and control as well as construction management. Since then, Burgess Services has worked on such projects as the Westin Hotel at the Denver Airport and the City and County of Denver Justice Center. Additionally, Burgess would go on to become the first female Black chair of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce.

Patricia Billings

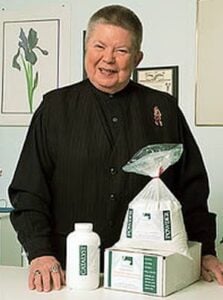

In 2020, Patricia Billings, inventor of Geobond, was named one of the "37 Women Who've Upended Science, Tech, and Engineering For the Better" in Popular Mechanics.

In 2020, Patricia Billings, inventor of Geobond, was named one of the "37 Women Who've Upended Science, Tech, and Engineering For the Better" in Popular Mechanics.A truly unlikely innovator, Billings got her start studying art at Amarillo College, where she would fall in love with creating sculptures. She used plaster of Paris to craft these sculptures and eventually opened a storefront in Kansas City, Missouri to sell her artwork.

During this time, Billings was working on a swan sculpture, which took her a total of four months to complete. But when she finished, it suddenly broke apart and shattered into pieces. Billings was furious at the massive loss of time and resources, so she decided that she would create a stronger substance than plaster of Paris for her sculptures. She started researching materials used in the Renaissance Era and discovered that the plaster that had been used in frescoes was strengthened with a cement-like additive to extend the longevity of their plaster. She ultimately spent eight years of trial and error before finally hitting upon the correct mixture. She then created a ten-foot statue and sent it to a science lab for tests, who then passed it on to the U.S. Air Force, who discovered that the product—which Billings called “Geobond”—was fire-resistant. It was so fire-resistant that it wouldn’t burn even at temperatures of 6,500 degrees Fahrenheit.

Geobond ended up being the first safe alternative to asbestos. Although asbestos was also fire-resistant, it was restricted in building use after the 1970s when it was found to cause cancer. Even better, Geobond was capable of being molded into dozens of different forms and textures and could be used in place of tile, marble, and even breaks—something asbestos couldn’t do.

Although Billings now has two patents on her invention, she never revealed the exact recipe behind Geobond. She even turned down a multi-million offer to buy the recipe. Nevertheless, Geobond has transformed the construction world as we know it and is a common material today.

-1.png?width=112&height=112&name=image%20(4)-1.png)